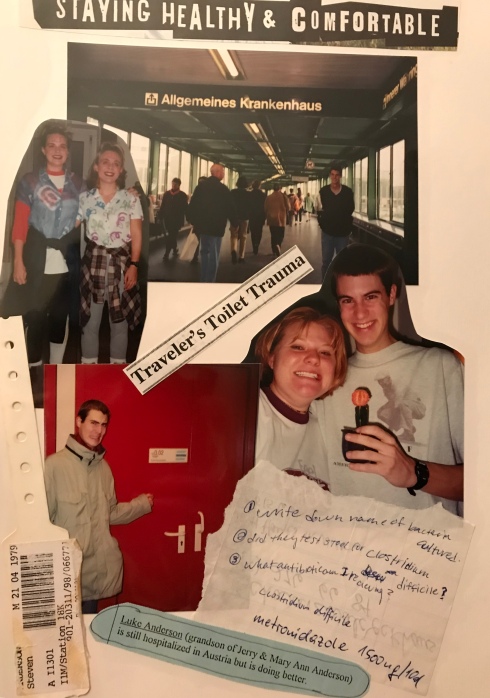

In the last blog, I talked about experiencing the most embarrassing that can happen to you when I was in Germany. Not long afterwards, I experienced the worst thing that can ever happen to your mom when you are studying abroad: I got sick. Really sick. Like had to be carried and or wheeled around sick. Ten days in the hospital in a foreign country sick.

I’m not sure when it started. I’m guessing it was that really bad pizza I ate in London, or maybe the questionable McDonald’s in Paris. Regardless, my stomach declared war on the food, and then it declared war on me for the next few weeks as punishment. Being my mother’s child, I came fully prepared with an arsenal of medicines for any possible ailment, ranging from bee stings to bubonic plague. I started with a barrage of over-the-counter drugs I was confident would end the skirmish before it really took off. I underestimated my foe.

Interestingly enough, I might not have been the only one suffering gastrointestinal battles, as around the same time my journal starts mentioning my stomach hurting regularly, it also mentions the “Great Fart of 18:39” from 9/12 on a bus through Germany. Apparently, it was the “WORST THING I’VE EVER SMELLED” and wiped out 8-10 rows of us – even the one who committed the foul deed was choked up by the noxious fumes. I won’t mention the specific party by name, but his initials sound like a fast food chain that serves roast beef…

The next day’s journal entry mentions the war with my stomach ratcheting up a few notches, with diarrhea six or seven times that day. It got to the point that my drugs clearly weren’t doing the trick, so I phoned in reinforcements in the form of a family doctor back home. He gave me some advice, and I marched on confident of a swift victory. Again, wrong.

Three days later, my journal said it was the “WORST DAY OF MY LIFE” (Can you say drama queen? Why was I always yelling in my journal?). Not only was I having severe diarrhea regularly, but now I was having severe cramping. I called Dr. Mitchell back home, and he said I needed to go see a doctor in Vienna. Our sponsor had the contact information of an American doctor, and so he took me to see him.

Before I talk about my diagnosis, I want to mention some questions I’ve thought about in retrospect that I should’ve asked then, such as: 1) Why are you practicing abroad and not in America? 2) Are you still allowed to practice in America? 3) Did you do anything illegal/unethical that caused you to take a trip abroad and just never come back? 4) Are you actually a doctor of medicine, or do you just have a doctorate in philosophy and a Mayo Clinic book? You see the foreshadowing here. He was clearly a double agent working for the opposition.

My diagnosis was that I had a bacterial infection, a fever, and I was dehydrated. He gave me a shot in the butt, some antibiotics, and sent me on my way. I was so exhausted, I didn’t think I’d make it home. That night, I was so feverish that I just laid awake shivering under the covers. I still was getting up “every five minutes” to go to the bathroom, and the last two times I had blood in my stool. I looked at the mirror in my reflection and got scared because the battle had taken its toll. I looked pale and gaunt, but my cheeks were flushed with fever. I missed my mom because she would’ve been there with a cold rag to help assuage my condition. I finally fell asleep.

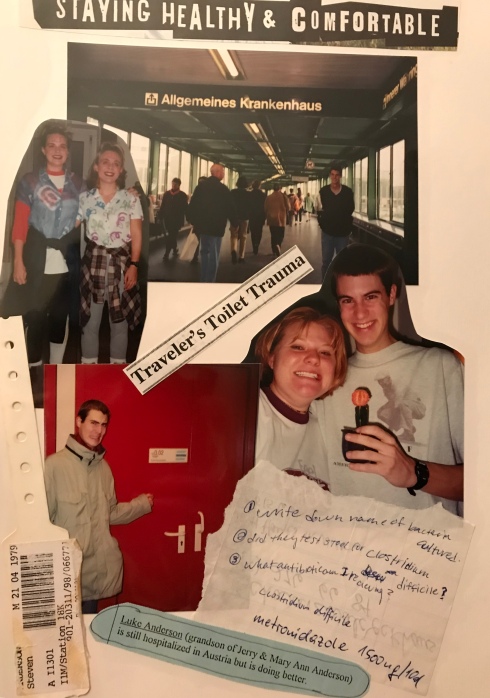

As it turns out, Dr. Quack had given me drugs that killed all the good bacteria in my intestines and left the bad bacteria to take over and crush my will to live. A few nights later, I was physically unable to move to go to the bathroom any more, exhausted from not sleeping much, dehydrated, and still feverish. And so, on 9/20, I waved the white flag and asked to go to the krankenhaus (hospital) because I was very krank (sick). I remember they had to physically carry me down to the cab because I was too weak to walk, and was worried that they would speak enough English for us to communicate at the hospital. The rest was a blur for the next few days.

My only memories of my first 48 hours in the krankenhaus were a mix of the snoring of my two roommates (whom I named Dr. Buzzsaw and Herr Hairball), having to be wheeled to the bathroom on the regular, and awaking once in my own mess.

Sometimes, I would wake up disoriented because it all seemed like a dream between the unfamiliar place and everyone speaking German. I actually started dreaming in German because I was so submerged in it. The doctors spoke English when they came to check on me, and most of the nurses would try with their broken English, but the only regular mother tongue I experienced was when I got well enough to go down the hall to the room with the television. If I turned the sound up over the dubbing, I could get Cartoon Network loud enough to hear the English dialogue. I’ve never been so happy to hear Foghorn Leghorn’s southern drawl or Shaggy’s cowardly retorts to Scooby.

I also vividly remember that it was a teaching hospital like on Grey’s Anatomy. Why do I remember this random detail? Well, I’m a touch needle phobic from a traumatic childhood injury, and so I remember a very nervous intern approaching me with a needle about day four. He needed to put in my IV for the day, and he was shaking as he reached for my arm. I have very skinny arms and very giant veins, so a blind nurse could get an IV in my arm, but he missed four times. I almost threw up, and finally told him that he was going to have to get someone else before he made me sick. I felt bad, but he needed to go find another pin cushion without childhood trauma to learn on.

In addition to my first experience with a teaching hospital, it was my first interaction with socialized medicine, which was fascinating to me. While one of my roommates was a burn victim – watching, and smelling, dressing changes was not so wonderful – the other was a younger man who would leave every morning, and then return in the evening, get medicine, and then go to sleep in the bed at night. I wished I could’ve spoken enough German to ask him what was going on, where he went every day, and why he needed to stay in the hospital overnight when he seemed fine to come and go as he pleased. I realized that they are much more cautious with sending you on your way under this system when, after I was feeling better a few days in, I was informed that I would be staying ten days total before I would be released. Um, say what? By the end of the experience, I was leaving in the morning, going all the way back across town, attending class, grocery shopping, eating pizza at my favorite spot, and then coming back to sleep there at night like my roommate. In America, I probably would have been there two nights and then sent home.

The thing I remember the most about my hospital stay, however, was the care and concern shown to me by so many people. Lindy Adams, one of our sponsors, was a saint and came to see me every day. Her daughter, Liz, made a card for me and had everyone sign it. Most of my travel mates came to visit me, some very regularly. They brought me little gifts, like a cactus or a bucket of Tichy Eis (ice cream) to share, or they dressed up to make me laugh. My mom and dad called every day, and it was all everyone could do to keep my mom from hopping on a plane to be with me. My grandparents called regularly, and many friends from school called to check on me back when international calls were not so cheap and there was no Skype. My mom sent a giant care package that I was sure to note in my journal cost “$117!!!” to ship. I was in no short supply of love, and that assuredly helped me heal more quickly.

In the end, I reflected in my journal that this experience had taught me patience. In retrospect, I think I learned that I need to take care of and listen to my body instead of pushing it so hard. And, most importantly, the Austrians and their socialized medicine seemed to know something that us Americans don’t always understand: healing takes time, even when you look fine on the outside, so take your time at the krankenhaus.

When we were looking down into the Forum from the Palatine Hill, Mitch pointed out a pair of green doors on a church much higher than the base of the ancient columns in front of it. Apparently, the church was built much later, after the Forum had been mostly buried under centuries of rubble and neglect. He said it was even referred to as the “cow field” for a while, years after being the center of Roman life. They only began excavating it all slowly, but surely, a few centuries ago.

When we were looking down into the Forum from the Palatine Hill, Mitch pointed out a pair of green doors on a church much higher than the base of the ancient columns in front of it. Apparently, the church was built much later, after the Forum had been mostly buried under centuries of rubble and neglect. He said it was even referred to as the “cow field” for a while, years after being the center of Roman life. They only began excavating it all slowly, but surely, a few centuries ago. While starting as a symbol of Rome’s grandeur in the 1st century A.D., full of gladiator combat and man vs. beast tests of will, it began to decline with alongside the might of Rome. Over time, fires, earthquakes, and raiding took their toll on it’s once grand physique. The last recorded events in the ancient Colosseum were in the 5th century.

While starting as a symbol of Rome’s grandeur in the 1st century A.D., full of gladiator combat and man vs. beast tests of will, it began to decline with alongside the might of Rome. Over time, fires, earthquakes, and raiding took their toll on it’s once grand physique. The last recorded events in the ancient Colosseum were in the 5th century.

. The last angel on the bridge held a spear in a fearsome pose, as if guarding the fortress by himself. My mind started asking a million questions. How did the fortress stay in the church’s hands if the Vatican area close by fell? Would they just hunker down there and beg other Catholic countries to come save them? How much food did they keep there regularly, and for how long could they hold out? Mitch later showed us the passage the pope would use to escape to the fortress from the Vatican, high above the crowds below.

. The last angel on the bridge held a spear in a fearsome pose, as if guarding the fortress by himself. My mind started asking a million questions. How did the fortress stay in the church’s hands if the Vatican area close by fell? Would they just hunker down there and beg other Catholic countries to come save them? How much food did they keep there regularly, and for how long could they hold out? Mitch later showed us the passage the pope would use to escape to the fortress from the Vatican, high above the crowds below. Later, she was joined by a cacophony of other birds beginning their morning rounds – some more pleasant than others. So, I wearily joined them in their greeting of the day, a strange role reversal since Mitch was still asleep.

Later, she was joined by a cacophony of other birds beginning their morning rounds – some more pleasant than others. So, I wearily joined them in their greeting of the day, a strange role reversal since Mitch was still asleep. Later, when walking through the city, it dawned on me that I was last here in November, not June, and so I saw a very different place. The Rome of summer is vibrant with color. Green ivy crawls up the sides of posh hotels and ancient columns. Bright red and pink flowers can be found throughout the city decorating window boxes of third floors, hanging off of black wrought iron terraces. Yellow flowers punctuate the walk along the ancient Forum roads.

Later, when walking through the city, it dawned on me that I was last here in November, not June, and so I saw a very different place. The Rome of summer is vibrant with color. Green ivy crawls up the sides of posh hotels and ancient columns. Bright red and pink flowers can be found throughout the city decorating window boxes of third floors, hanging off of black wrought iron terraces. Yellow flowers punctuate the walk along the ancient Forum roads. I now understand that Rome held secrets I wasn’t ready for at 19. Life can’t be planned like the gridded layout of a flat Oklahoma town. Having a rich history means sometimes tearing down or building around the old, appreciating the ruins from your life that serve as reminders of better times to inspire hope, or of darker times to keep you from repeating past mistakes.

I now understand that Rome held secrets I wasn’t ready for at 19. Life can’t be planned like the gridded layout of a flat Oklahoma town. Having a rich history means sometimes tearing down or building around the old, appreciating the ruins from your life that serve as reminders of better times to inspire hope, or of darker times to keep you from repeating past mistakes.