It was the first time it had ever happened, so it was unsettling. What in the world was going on?

At the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, Monet grabbed me by the lapels and dragged me into one of his paintings. I stood, transfixed, unable to move on with the rest of the tour group as they traveled on through the rest of the Impressionists.

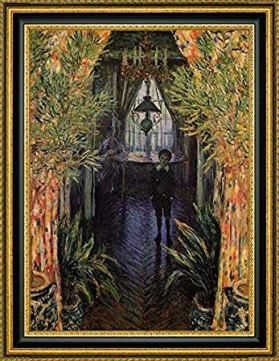

The protagonist of A Corner of the Apartment was staring at me, and I couldn’t break his gaze. He was a little boy, in what appeared to be a school uniform, standing in the middle of a room, hauntingly isolated despite the matronly figure in the distant background, head cocked slightly to one side. I felt like I knew him, and he was wanting to say something to me. I stood there for maybe 10 minutes, trying to listen, yet unable to hear him. What did he want to tell me? Was it important? How could I coax the words out? But I couldn’t hear him, no matter how hard I tried.

Eventually, I moved on to the next room, but my mind kept drifting back to the painting. I was fascinated by the experience. How could something painted 123 years before speak to me like this? I had never had such a strong reaction to a painting before. Was this normal? Did other people have this happen to them?

And then, it happened again a few rooms later when The Dream by Detaille sucked me in. As the French soldiers slumbered behind battlements, their dreams of glorious victory played out in the clouds above and I became one of them. I long stood daydreaming alongside the sleeping soldiers, hearing bugle calls and horse hooves and drumbeats and Les Miserables anthems driving me onward. Finally, I shook my head and broke the spell Detaille had cast, returning me to a room in a museum from my mental field trip to a French countryside battlefield.

Weird.

I didn’t know what to make of the experience at the time, for art had never moved me or stirred me in such ways. Maybe it’s because I had primarily experienced it through the pages of textbooks or the art anthologies I’d regularly thumb through at Barnes & Noble. I’ve come to discover that a photographic copy robs art of much of its true power. You can’t see the brilliance and depth of the colors or the magnitude of a painting that takes up a giant swath of wall space. The printed page neuters the art experience in a way, making it safe and sedate and, all too often, lifeless.

Later in the trip, the same experience with art happened again and again as I encountered the masters in person. I crept through the darkness with Rembrandt’s The Night Watch or covered my ears to stop the piercing sound coming from the mouth in Munch’s The Scream. Even within the last year, I have been lulled into a tranquil bliss by Monet’s The Path Through the Irises and horrified by the ravages of war as depicted by Sargent’s Gassed.

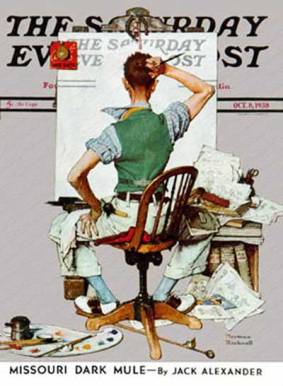

Perhaps the most significant time an artist spoke to me was when I had a chat with Norman Rockwell at the Frist in Nashville almost five years ago; we talked about writer’s block when I was looking at his Blank Canvas for the Saturday Evening Post cover from 1938. I’ve been there so many times, scratching my head in the same way with my similarly skinny arm poking out from a rolled-up sleeve, trying to get something to come out when nothing will, frustrated and helpless. I sat and commiserated with Rockwell for quite some time before going home and writing a blog post about it, ironically inspired. That summer, accidentally running across a handsome stranger re-enacting that very painting for his profile picture changed my life.

But none of that would’ve happened if it wouldn’t have been for Monet, over a century ago, painting something universal enough for me to connect with as I stood there twenty years ago in Paris. I still can’t explain why that little boy haunted me so.

In retrospect, after my experience in London, maybe he was me.